EL USS MEMPHIS (Ex Tennesee)

Por Luis Jar Torre - Publicado en la Revista General de Marina de España Agosto-Septiembre de 2004 y en http://www.grijalvo.com/index.htm-

Don Juan Manuel Grijalvo tiene un magnifico sitio web en http://www.grijalvo.com/index.htm. Entre los muchisimos articulos que hay allí y que vale la pena explorar, hay una serie correspondiente a las notas que el oficial de la marina española, ex marino mercante, ex Capitán de Puerto y ex Inspector de Seguridad Marítima don Luis Jar Torres escribiera para la Revista General de Marina, de España. Nos han otorgado permiso para publicar algunas de sus historias, entre las que se encuentra ésta. Recomiendo que lean directamente de Grijalvo las correspondientes a accidentes, en el indice: http://www.grijalvo.com/Batracius/y_presentacion.htm

En un mercante de cuyo nombre no quiero acordarme, navegaba no hace muchos lustros un capitán que en sus visitas al puente solía quejarse de lo “aleatorio” de su oficio. Siendo persona inteligente su propio intelecto le había llevado al miedo de la mano de la imaginación y, mucho antes de enfrentar su enorme buque a una recalada particularmente difícil o un río especialmente retorcido, desfilaban por su mente todas las cosas que podían salir mal y costarle el cargo. Conforme se acercaba la fecha fatídica le invadía una ansiedad que, a veces, combatía ingiriendo potentes destilados etílicos de extraña eficacia, pues en dos ocasiones fui testigo durante mi guardia de cómo, recuperado el uso de los sentidos, su problema había quedado milagrosamente por la popa a costa de la ansiedad ajena. Por lo demás, y como suele suceder con los derrotados, era una persona a la que resultaba fácil tomar afecto. Años después me enteré que la etiqueta naval exigía desear “buena suerte” al nuevo comandante de un buque de guerra, constatando así que el pobre hombre no andaba tan desencaminado con sus quejas y que la “aleatoriedad” era un problema muy común. Por fortuna, algunos ya estábamos prevenidos sobre sus causas gracias a la sabiduría de otro capitán que, en sus clases de Economía Marítima, nos reveló que el problema del Seguro Marítimo radicaba en la “viscosidad del medio” (era vizcaíno). Oleadas de cruceros En 1888 los franceses pusieron de moda el crucero acorazado y la marina norteamericana, que en esa época no dictaba normas sino que las adoptaba, también lo incorporó. Según las malas lenguas su primer “modelo” (¡el “Maine”!) habría sido una mala copia, sus raquíticos 17 nudos obligaron a “reclasificarle” en 1894 como acorazado... de “segunda clase” por su escuálido blindaje. Tras el “Maine” los norteamericanos construyeron otros dos “Armoured Cruisers” (el “New York” y el atípico “Brooklyn”) y así llegaron a la guerra Hispano-Norteamericana, pero cinco meses después de que el “Maine” se desintegrara en La Habana los británicos pusieron la quilla del primero de los seis cruceros tipo “Cressy”. Eran unos buques destinados a pasar a la historia en 1914 cuando un único submarino despachó a media serie en menos de una hora (el “Cressy”, el “Hogue” y el “Aboukir”), pero a finales del siglo XIX resultaban asaz aparentes y el modelo intrigaba a los diseñadores navales norteamericanos. Según parece, fruto de esta intriga nacieron los “Big 10”, una decena de magníficos cruceros acorazados compuesta por los seis “Pennsylvania” (puesta de quilla 1901-1902) y los cuatro “Tennessee” (1903-1905), casi idénticos pero muy mejorados. Cuando se entregó en 1906 el “Tennessee” (alias “Tenny”) representaba el apogeo de su especie: suficientemente armado y protegido para dar un repaso a cualquier crucero y suficientemente veloz para aventajar a cualquier acorazado, pero a despecho de su velocidad llegó tarde. Mientras tanto, en febrero de aquel mismo año los británicos sacaron de la manga el primero de sus acorazados tipo “Dreadnought”, de similar velocidad pero (obviamente) muy superior “musculatura”, y fue el propio concepto de crucero acorazado lo que quedó anticuado. Con el tiempo surgiría la “contramedida” (el crucero de batalla, como el “Hood”), la “recontramedida” (el superdreadnought, como el “Bismarck” que hundió al “Hood”), la “archicontramedida” (el portaviones, como el “Ark Royal” que se hundió al “Bismarck”) e incluso algún molesto pigmeo (el submarino, como el U-81 que hundió al “Ark Royal”) pero en 1906 los propietarios del “Tennessee” tenían motivos para sentirse ufanos. Se trataba de un buque de 153,7 metros de eslora, 22,2 de manga y 7,62 de calado con un desplazamiento máximo de 15.715 toneladas que montaba cuatro piezas de 254 mm en dos torres dobles, dieciséis de 152 mm (doce en los costados), veintidós de 76 mm, alguna pieza menor y cuatro tubos lanzatorpedos; la protección de costado era de 127 mm y la horizontal oscilaba entre 102 y 38 mm. Para mover tanto hierro había dieciséis calderas, dos enormes máquinas alternativas y dos ejes que podían dar unos 23.000 IHP y 22 nudos sin forzar mucho la cosa; naturalmente, la “cosa” funcionaba a base de carbón y la dotación rondaba las 900 personas. En uno de estos buques (“Pennsylvania”, 1911) se efectuaría la primera toma a flote de un avión, y en otro (“North Carolina”, 1915) el primer despegue con catapulta. El “USS Memphis” (todavía “USS Tennessee”) cruzando la esclusa de Pedro Miguel en el Canal de Panamá. Esta fotografía está obtenida casi con certeza el 27 de Abril de 1916, de regreso de la comisión a Sudamérica y cuatro meses antes de su pérdida en Santo Domingo. (Foto Naval Historical Center USA)

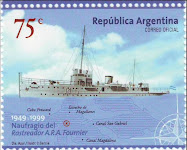

El “Tennessee” llegó a Nueva York en julio de 1915 y, antes de entrar en obras en septiembre, todavía realizó cuatro viajes a Haití con otros tantos cargamentos de marines. Finalizadas las obras en enero de 1916, el crucero volvió a Haití relevando como buque insignia de las unidades allí destacadas a su gemelo el “Washington”, que también tenía que entrar en obras y cuyo comandante pasó a mandar el “Tennessee” por su conocimiento de la situación local. Y así entra en nuestra historia el capitán de navío Edward Latimer Beach. El buque fue enviado a una tournée sudamericana de camino a la Alta Comisión Internacional que se reunía en Buenos Aires. En Norfolk embarcaron diecinueve estadistas y diplomáticos, destacando entre ellos el Secretario del Tesoro McAdoo con su esposa, que era la hija del Presidente Wilson. Tras pasar dos meses haciendo escala en cada puerto (en Trinidad les visitó Teddy Roosevelt), estrechando relaciones diplomáticas, regresaron a casa el 4 de mayo vía Estrecho de Magallanes y Canal de Panamá. A poca suerte que tenga, cualquier comandante saldrá de una comisión así con la agenda muy “mejorada” y su “cotización” en alza, aunque Beach ya cotizaba en máximos. Tenía entonces cuarenta y nueve años y un historial que incluía su presencia en la batalla de Cavite, un mando a flote durante la crisis de Veracruz, una considerable producción literaria y una mentalidad moderna; irónicamente, la ruina de su carrera se achacaría a un hecho natural. En aquellos años Norteamérica construía acorazados en serie, y ante la creciente “demanda” de nombres de estados, los ocho cruceros hubieron de cambiar los suyos: a su regreso de Sudamérica el “Tennessee” pasó a llamarse “Memphis”, con disgusto de su tripulación, por aquello de la mala suerte que implica un cambio de nombre. En Julio de 1916 y ya rebautizado el crucero zarpó de nuevo en patrulla de paz, esta vez a la República Dominicana. En plena Gran Guerra y recién inaugurado el Canal de Panamá, sus accesos habían adquirido gran importancia para los EEUU, poco partidarios de que ante cualquier revolución latinoamericana una potencia “incorrecta” sentara sus reales en el lugar “inadecuado”. Basta mirar un mapa para ver que, con Cuba y Puerto Rico bajo control norteamericano y la parte este de la “muralla” del Caribe cubierta por el Reino Unido (Trinidad) y Francia (Antillas Menores), quedaban dos “agujeros” por cubrir: las Islas Vírgenes (Dinamarca) y La Española (Haití y República Dominicana). En el primer caso se optó por “comprar” hábilmente el archipiélago (1917) sin considerar el detalle de que no estaba en venta; en el segundo el agujero se “tapó” directamente con marines. Oleadas de marines Quince años después de que Teddy Roosevelt definiera su famosa política del “Gran Garrote” (“Speak softly and carry a big stick”), la práctica totalidad de las repúblicas caribeñas presentaba hematomas en su soberanía o huellas de marines en sus playas, pero la sintomatología de Haití y la República Dominicana era francamente preocupante. En 1912 el presidente haitiano había volado por los aires junto con su palacio presidencial y pasados tres años y cinco presidentes, el 28 de julio de 1915 otro acabó su carrera a manos de una multitud que le hizo pedazos; aquella misma tarde el crucero “Washington” entró en Puerto Príncipe, iniciando una ocupación militar que duraría hasta 1934. En la República Dominicana el problema era serio pues, a resultas de su enorme deuda externa y ante la amenaza de que los acreedores europeos intervinieran militarmente en su “patio trasero”, los EEUU habían embargado en 1905 las rentas de la Aduana destinando la mitad de sus ingresos a amortizar la deuda (hoy equivaldría a embargar el Ministerio de Hacienda). Tras el intento de imponer un “consejero financiero” norteamericano para gestionar también la otra mitad, en 1916 se produjo un golpe de estado y la intervención no solicitada de las fuerzas navales yanquis. Nominalmente actuaban en apoyo del gobierno, pero entre dimes y diretes el país se llenó de marines y, oportunamente, el 18 de agosto el Receptor General de Aduanas (norteamericano) comunicó que no habría más entregas de fondos al gobierno local hasta no llegar a “un completo acuerdo en cuanto a la interpretación de ciertos artículos”. (Ver Actividades navales en Sudamerica y "Fraternidad Argentino-Dominicana") Absolutamente sin fondos, el gobierno licenció al ejército por no poder pagarle y la administración languideció hasta que, el 29 de noviembre de 1916 y a bordo del crucero “Olympia” fondeado en Santo Domingo, el capitán de navío Knapp declaró la ocupación militar bajo su mando. En buena lógica esta declaración debería haberse hecho a bordo del “Memphis”, y quizás por su comandante, pero el capitán de navío Beach andaba entonces ocupado en “declaraciones” de naturaleza muy diferente. El “Memphis” había fondeado en Santo Domingo el 23 de julio con ánimo de quedarse y con un contralmirante a bordo (Charles F. Pond, Jefe de la División de Cruceros de la Escuadra del Atlántico). Además de la consabida historia de mantener la paz, su misión era dar apoyo a la fuerza de marines allí desplegada y actuar como buque de protección, supondremos que frente a “mantenedores de la paz” de terceros países. Su llegada coincidió con el inicio de la “temporada alta” de huracanes y, en principio, el comandante Beach decidió mantener encendidas cuatro calderas para poder cambiar de aires con rapidez si la cosa se ponía difícil, pero aquel año se realizaban economías, y el contralmirante Pond le “convenció” de que dos calderas encendidas y cuatro en “stand by” serían suficientes. El 22 de agosto por la tarde y mientras el almirante agasajaba a bordo (con cena y película) al representante norteamericano, el barómetro cayó repentinamente y, sospechando que un huracán rondaba su carrera, Beach canceló la “sesión de tarde”, ordenó encender calderas suplementarias e izar las embarcaciones menores, por lo que el almirante tuvo que explicar a su invitado la conveniencia de dormir a bordo. El huracán no llegó y al día siguiente el diplomático fue devuelto a tierra tras disfrutar un “reality show” a falta de película; no nos consta su reacción ni si el almirante hizo una “edición especial” de los informes personales de Beach, pero creemos que este último tenía razón por dos motivos: primero porque en los trópicos la presión atmosférica es mucho más estable que en nuestras latitudes y, en temporada de huracanes, cualquier desviación de la media es para echarse a temblar. Desastres protocolares aparte, la “movida” sirvió al menos para comprobar que con dos calderas encendidas y cuatro en “stand by” se podía levantar presión en 40 minutos, un plazo en apariencia razonable y en esta tranquilidad pasó otra semana hasta que el martes 29 de agosto amaneció un día estupendo con una ligera brisa del noreste. A mediodía el termómetro marcaba 26º, dos menos de lo habitual. El “Memphis” seguía fondeado a media milla de tierra, en 17 metros de fondo y con nada menos que 128 de cadena, lo que indica que Beach no se chupaba el dedo; en realidad le habían asignado por tiempo indefinido a un mal fondeadero situado en la desembocadura de un río, completamente abierto desde el este al oestesuroeste y en una zona donde los vientos dominantes eran del este a 12 nudos en agosto.

Cañonero "Castine" (De US Navy Historical Center Photo - [1] from http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/c4/castine-ii.htm, Dominio público, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1400671) En la desembocadura del río estaba el centro histórico de Santo Domingo (ver gráfico) y la fortaleza Ozama, coyunturalmente ocupada por los marines y convertida en “Fort Ozama”, y entre dicha fortaleza y el “Memphis” (a unos 500 metros del crucero) estaba fondeado el cañonero “Castine”, un cascajo de 22 años que había tenido que ser cortado en dos y alargado hasta los 62 metros de eslora para hacerlo más estable. A su comandante (capitán de fragata Bennett), además de haberle tocado la desgracia de mandar un barco tan feo, aquel día le tocaba abrir la boca ante el dentista del “Memphis” y su lancha llegó al portalón diez minutos antes de que (a las 1300) salieran hacia tierra el equipo de béisbol del crucero y algún “franco de paseo”. También el almirante salió “franco”: en principio él y el comandante estaban invitados a un concierto en la catedral a primera hora de la tarde pero, hábilmente, Beach alegó trabajo pendiente y Pond desembarcó acompañado de un par de ayudantes para, ya en tierra, reunirse con el cónsul norteamericano antes del concierto. En el “Memphis” la cosa empezó a torcerse hacia las 1515 horas y, naturalmente, el problema fue detectado en el acto por el segundo comandante, capitán de corbeta Williams, que supervisando el adrizamiento de un chinchorro se percató de un atípico balance. Era habitual que el buque se moviera por las tardes al arreciar la brisa (debía atravesarle a la mar), pero en aquel momento no había viento y cuando Williams echó un vistazo al barómetro comprobó que marcaba 30,09 pulgadas (1.019 milibares), 4 milibares por encima de la normal para esta zona en agosto. Si la lectura del barómetro tranquilizó a Williams, la mar de leva que estaba empezando a colarse en el fondeadero no le gustó nada y, tras enviar un par de botes a tierra para recoger a los francos, le fue con su informe al comandante. El del “Castine” ya había terminado su sesión de tortura y estaba haciendo una visita de cortesía a Beach, así que cuando Williams transmitió a éste su inquietud salieron los tres a cubierta: hacia alta mar se veían olas de considerable tamaño acercándose desde el sureste, el “Castine” daba serios bandazos y, en tierra, estaba formándose una peligrosa rompiente. Ambos comandantes debieron pensar lo mismo y, mientras Bennett salía en una lancha hacia su buque, Beach ordenó levantar presión en las calderas; eran las 1530 y por fuerza hubo de pensar que de salir todo como en el último “ejercicio” tendría presión hacia las 1610. Una de las lanchas enviadas por el segundo ya había entrado en puerto pero, visto el aspecto que tomaba la rompiente, el comandante ordenó hacer regresar a la que todavía estaba en camino; antes de que pudiera izarse la señal la embarcación también cruzó la barra y se coló en el río, por lo que Beach ordenó hacer señales a la guarnición de “Fort Ozama” en el sentido de retener en tierra ambas embarcaciones y personal anexo. Oleadas de olas A partir de las 1530 y mientras la dotación arranchaba el crucero a son de mar la cosa empezó a ponerse fea; el problema era un horrible balance que, además de disminuir la eficiencia del carboneo “manual” de las calderas, hacía que algunas olas que ya empezaban a romper lo hicieran en la cubierta de botes, enviando cascadas de espuma a través de los ventiladores y “apagando” los ánimos de personal y material. Se suponía que tapar dichos ventiladores era trabajo de los chicos de máquinas, pero por allí todo el mundo andaba paleando carbón (¿mojado?) y, a su solicitud, un equipo de cubierta solventó el problema como pudo. El comandante fue informado de que no habría presión hasta las 1635. En una novela hubiera quedado bien decir que el rugido del viento ahogó su respuesta, pero la realidad es que ni entonces había viento ni fue precisamente su voz lo que acabó por ahogarse. Ante la imposibilidad de izarlas por el balance, ni enviarlas a puerto por la rompiente, dos embarcaciones más del “Memphis” y otra del “Castine” habían sido despachadas fuera de la rada con idea de recogerlas en sondas mayores y con olas más manejables, pero alrededor de las 1600 horas los pasmados ocupantes del crucero vieron cómo su atiborrado bote a motor aparecía por la boca del río de regreso a bordo, una maniobra carente de sentido por la imposibilidad de izarlo, pero ni siquiera hubo ocasión de hacer el intento porque a mitad de camino la embarcación zozobró causando la muerte a 25 de sus 31 ocupantes. La lancha había naufragado a unos 300 metros del “Castine” y más hacia tierra justo cuando, tras levantar una precaria presión, su comandante se disponía a abandonar el fondeadero; Bennett intentó ayudar entrando en rompientes peores que las que trataba dejar atrás hasta que, tras arrojar algunos salvavidas a los náufragos, se vio forzado a salir a alta mar para evitar que su dotación y él mismo acabaran uniéndose al grupo. Quienes lo vieron pasar desde el “Memphis” dijeron que el viejo cañonero presentaba un aspecto lamentable con su cubierta arrasada, escupiendo agua por los imbornales y resoplando mientras se arrastraba a la raquítica velocidad de 9 nudos, pero hubo quien apuntó que en aquel momento la velocidad máxima del “Castine” era nueve nudos superior a la del “Memphis”. Un barco en apuros suele tener peor aspecto visto desde fuera que desde dentro aunque, con la cubierta casi permanentemente bajo las olas, la situación del “Memphis” empezaba a ser catastrófica desde cualquier punto de vista; los relatos mencionan algún balance de 60º, pero quizá solo fuera una estimación porque más allá de los 45º la vida a bordo carece de otro sentido que la mera supervivencia. Sirva de ejemplo lo ocurrido al desdichado segundo, literalmente noqueado tras ser lanzado por los aires y estrellarse contra unas taquillas. Respecto al tamaño de las olas, se dijo que hacia las 1545 el comandante pudo ver como una de más de 20 metros se acercaba por alta mar desde el este oscureciendo el horizonte, existiendo referencias posteriores a otras de similar tamaño en el fondeadero. Observando la carta con detenimiento se ve en aquel lugar el fondo cae de los 17 a los 100 metros de profundidad en apenas 400 (ver gráfico), es decir, que Beach estaba fondeado precisamente sobre la parte alta de un talud completamente abierto al mar dominante (este): un paraíso para surfistas. Puestos a ser rigurosos hay que reconocer que una ola de tales dimensiones que se hubiera colado en 1916 en la rada de Santo Domingo habría dejado un reguero de tinta, y no fue el caso: los cuatro registros regionales que hemos podido consultar mencionan inundaciones por tsunamis y huracanes anteriores y posteriores, pero aquel 29 de agosto ningún suceso extraordinario evitó al Almirante Pond tragarse en su totalidad el concierto y finalizar la comisión a las 1630 horas con el uniforme seco. Es una obviedad decir que, en “temporada alta” y en el Caribe, ante una enorme mar de leva siempre hay que pensar que un huracán anda suelto (toca uno al mes), pero una mar tendida de más de 12 metros exige longitudes de onda extraterrestres y, además, la movilidad y continuo rolar del viento en un huracán reducen su “fetch” al extremo de que la mar de viento generada raramente sobrepasa dicha altura aunque, eso sí, son olas como paredes. La mar de leva resultante suele tener un período extraordinariamente largo (unas cuatro olas por minuto). Por cierto que al segundo del “Memphis”, le hubiera encantado saber que actualmente se consideran premonitorios de un huracán todavía muy lejano una mar “extra-larga” y un “sube y baja” del barómetro (¡si solo baja es que anda cerca!); lo dice el mismo manual de su “empresa” que recuerda que la interacción de una ola con el fondo está en función de su longitud de onda, algo que convierte al mar de leva de un huracán en particularmente susceptible de arbolar al acercarse a tierra. Recordaremos a los no iniciados que, incluso una ola de “solo” 10 metros (relativamente inofensiva en alta mar), puede resultar peligrosa si nos sorprende a media milla de la costa, ganando pendiente, altura y a punto de romper: en tal situación puede tomarnos de proa y transmitir esfuerzos inadmisibles al casco, estrellarse contra el costado y hacernos zozobrar. Volviendo al “Memphis”, y para desesperación del comandante, a las 1635 la cosa seguía sin funcionar. La única razón para que a aquellas alturas no estuvieran ya en las piedras era la elasticidad aportada al fondeo por la enorme extensión de cadena pero, justo cuando Beach acababa de ordenar fondear otra ancla, avisaron de máquinas que habría vapor en cinco minutos. En una situación realmente desesperada uno puede temerse que le ordenen cualquier cosa, pero largar otra ancla en aquel escenario habría exigido sucesivos equipos de kamikazes por la rama de buceo para que, recuperada la propulsión, otro grupo de suicidas intentara filar por ojo todo el material. De hecho, creemos que sin propulsión y en términos de vidas humanas era mucho más rentable irse a las piedras que zozobrar donde estaban, porque con sondas de 17 metros y olas de más de 10, un buque de su eslora estaba listo a medio plazo. La dotación del “Memphis” lo descubrió cuando un golpe contra el fondo sacudió el casco; después la cosa fue en aumento y hacia las 1635 el pantoque sufría un golpe con el seno de cada ola que pasaba; debió ser hacia las 1640 horas cuando, a la vista de tres espantosas super olas que se echaban encima por estribor, Beach ordenó ciaboga sobre estribor y que la máquina respondiera al telégrafo para tomarlas más de proa. El resultado fueron unas paladitas de nada y un formidable golpe de costado que se llevó la cadena, el ancla o ambas cosas; se ha escrito que quienes estaban en el puente habrían visto la cresta de la ola unos 10 metros por encima de sus cabezas, lo que resulta creíble porque probablemente estarían en el seno, muy escorados a estribor y observando una ola que arbolaba. Al asistente del comandante se lo llevó la mar, el resto tuvo que refugiarse en el interior del palo de celosía para salvar la vida y cuando la tercera ola hubo pasado el “Memphis” ya estaba embarrancado y casi en tierra después de haber hecho el camino arrastrando y golpeando su casco contra el fondo; por un momento llegó a quedar apoyado sobre su costado de babor. De camino a tierra dos marineros intentarían efectivamente largar otra ancla: como era de temer, uno se fue por la borda y el otro, tras salvarse de milagro, consiguió su objetivo también con resultado previsible (salió hasta el último grillete por el escobén) pero, tecnicismos aparte, había que intentar algo y lo intentaron.

Oleadas de conjeturas Cuando se trata de explicar en dos palabras un desastre de este tipo suele recurrirse al socorrido “falló la máquina”, pero hay motivos para creer que aquí “los de máquinas” no fallaron en absoluto; a quienes sepan qué es y cómo se concede una Medalla de Honor del Congreso les bastará saber que, de resultas de este naufragio, se concedieron nada menos que tres y que las tres se las llevaron otros tantos maquinistas. Las citaciones hablan de personal atendiendo equipos a oscuras entre inundaciones de miles de toneladas de agua, calderas haciendo explosión y gente abrasada; otros relatos también mencionan emparrillados cayendo sobre la dotación, golpe contra el fondo que deformaban el casco y hacían saltar las líneas de vapor y, finalmente, otro que habría desplazado las máquinas con polines y todo, un cuadro que sumado a las “aguadillas” explica perfectamente la pérdida de potencia. Tras embarrancar hacia las 1645 horas, el mar que rompía contra su costado de estribor fue empujando al crucero hacia tierra hasta que, hacia las 1700 horas, otras tres super olas le incrustaron contra un acantilado bajo y allí se quedó, con la proa a unos 15 metros de tierra y la popa a otros 30. Pasados seis meses, y a despecho de sus 7,60 metros de calado, el “Memphis” estaba embarrancado en sondas de entre 3,60 y 5,75 metros; y el “aterrizaje” produjo otros ocho muertos y casi doscientos heridos, en buena parte por quemaduras en las salas de calderas. Durante un tiempo el crucero permaneció escorado a babor y balanceándose con cada ola hasta quedar inmóvil y casi adrizado al perder flotabilidad, pero mucho antes se había agrupado a la dotación en las cubiertas altas e iniciado el salvamento con ayuda de la población local, la guarnición de marines de Fort Ozama y los “francos de paseo” que habían salvado la vida por falta de espacio en la embarcación zozobrada; también estaba en el acantilado el contralmirante Pond, de regreso del concierto. El “USS Memphis” ya embarrancado; ambas hélices asoman fuera del agua y, sin contar las perforaciones, la popa parece estar clavada por unos 3 metros (en Santo Domingo casi no hay mareas). Obsérvese que pese al “revolcón” el crucero sigue teniendo un relativo buen aspecto gracias a la dureza de su piel (Foto Paul Siverstone Collection) Había saltado algo de viento y surgieron dificultades con las guías, pero gracias a los “francos” pudo tenderse un andarivel al que siguieron otros cuatro y al poco la dotación del “Memphis” desembarcaba al ritmo de cinco personas por minuto. Uno de los primeros fue el capitán de corbeta Williams, aún medio noqueado por el castañazo contra la taquilla, pero comisionado por Beach para organizar una recepción en tierra que se presentaba complicada porque los heridos representaban la cuarta parte de la dotación. Quienes no estaban en condiciones de agarrarse a un cabo fueron “transferidos” a tierra en sacos de carbón, aunque para “aterrizaje” peculiar el del barbero de a bordo, que acabó nadando con un mono a cuestas (ambos se salvaron). El “Memphis” estaba frente a un suburbio cuya iluminación dejaba bastante que desear, pero cuando cayó la noche había ya tal cantidad de mirones con automóvil que el salvamento pudo continuar a la luz de los faros hasta finalizar alrededor de las 2030 con el desembarco del comandante Beach dejando tras sí los restos de su carrera. Debió ser el momento más amargo de su vida, y lo habría sido más de haber sabido que a menos de una milla estaba desarrollándose la última parte del drama: las tres lanchas “rechazadas” habían conseguido alejarse hasta sondas que les permitían aguantarse a la espera de sus buques con relativa seguridad (a tres millas ya hay 500 metros), pero tras ver como el “Castine” se dirigía a alta mar y sin saber nada del “Memphis”, la noche se les echó encima. Desde su punto de vista tenían enfrente un “mar” de inquietudes con huracán incluido, teniendo a sus espaldas, la irresistible tentación del faro que balizaba la rada; resultó casi inevitable que poco antes de las 2000 horas las embarcaciones decidieran regresar a tierra y que, una tras otra, las tres fueran engullidas por la rompiente con el resultado de otros ocho muertos. Cuando acabó el oleaje también el “Memphis” era un caso perdido: en sondas tan escasas apoyaba sobre el fondo más peso del que jamás podría alijársele sin recurrir al soplete, y el roquedal descartaba dragar a su alrededor; además, pese a su buen aspecto exterior tenía la carena destrozada y la sala de máquinas hecha polvo, por lo que se comisionó al acorazado “New Hampshire” para hacerse cargo de la artillería y en diciembre de 1917 se le dió de baja. En enero de 1922 una crisis de optimismo induciría a una compañía de Denver a comprarlo como chatarra, pero cortar planchas de 127 milímetros tiene sus problemas y el “Tennie” siguió formando parte del paisaje hasta 1938.

Retirandole equipos y materiales, 1916

El destino de su último comandante fue aún más complejo: Beach era un firme candidato al almirantazgo, pero un crucero enviado para imponer respeto a todo un país estaba haciendo el ridículo encaramado a un barrio de su capital y urgía localizar un culpable. Nuestras fuentes son fragmentarias, pero a partir de este momento la cosa tiene todo el aspecto de un “tongo”; en el Consejo de Guerra que se le formó a Beach, su defensa “invitó” al contralmirante Pond a testificar sobre las instrucciones que le había dado acerca de no tener más de dos calderas encendidas en el fondeadero, pero Pond rehusó y Beach no permitió que fuera citado. En consecuencia, el comandante fue encontrado culpable de negligencia e ineficiencia, agraciado con la unánime recomendación de clemencia del tribunal y condenado a perder veinte puestos en el escalafón (¡ascenso a la basura!) para recibir acto seguido un importante mando en tierra (la Naval Torpedo Station, en Rhode Island), dieciocho meses después el del acorazado “New York” (a la sazón buque insignia de la flota norteamericana en Europa) y dejar el servicio activo en 1921 como Jefe del Arsenal de Mare Island... y con el empleo de capitán de navío. En su momento, el Secretario de Marina reduciría la pérdida de puestos a cinco y declararía que la tormenta que sufrió el buque del capitán Beach fue de origen volcánico y que solo era atribuible a un designio de Dios. A un marino prestigioso se le supone la ciencia infusa necesaria para sobrellevar un huracán o sus efectos, pero otro tipo de cataclismos permiten perder un buque sin que su comandante ni su país pierdan necesariamente su carrera. Las citaciones para la concesión de las tres Medallas de Honor del Congreso son claras (“...when that vessel was suffering total destruction from a hurricane while anchored off Santo Domingo”), pero a partir de aquí y hasta el día de hoy los medios “oficiosos” hablan de “tidal wave”, un término que en inglés resulta ambiguo por dársele habitualmente un uso inapropiado. En 1929, una cascara vacia, pero aun entera. Tras dejar la marina Beach ejerció de profesor de historia en la Universidad de Stanford hasta retirarse del todo en 1940. El capitán de navío Beach murió en 1943, y su trayectoria le retrata como una persona de capacidades tan extraordinarias como la mala suerte que salpicó injustamente el final de su carrera naval. Su hijo Edward siguió sus pasos con una carrera no menos notable: número dos de la Promoción del 39, durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial ganó una “Navy Cross”, dos “Silver Star” y otras dos “Bronze Star” como submarinista. Entorno geográfico y trayectoria del huracán: las características de la mar tendida están calculadas para un período de 15 segundos, muy habitual en estos casos. Se ha calculado un factor de amortiguamiento de 0,9 para una distancia de 300 millas y, dado que en huracanes de este tipo y edad no debe esperarse una mar de viento superior a 12 metros, lo previsible serían olas de hasta 11 a partir de las 1400 locales en aguas profundas frente a la rada de Santo Domingo (la mar de leva se desplaza a ½ de la velocidad teórica para una mar de viento idéntica). Quede constancia de que este tipo de olas se hacen inestables con pendientes entre 1/100 y 1/30 de su longitud de onda, por lo que son improbables alturas muy superiores. (Elaboración propia sobre contorno de costa NOAA/ U.S. Geologic Survey y trayectoria de NOAA/Unisys Corp.) En 1955 y siendo Ayudante Naval del Presidente Eisenhower escribiría un clásico sobre la guerra submarina (“Run Silent, Run Deep”) llevado al cine por Clark Gable y Burt Lancaster, pero saltó a la fama en 1960 cuando al mando del submarino nuclear “Tritón” (y con la bandera del “Memphis” a bordo) dio la primera vuelta al mundo en inmersión. Ya había mandado otros tres submarinos y un petrolero de flota y todavía le quedó tiempo para escribir otros doce libros, uno de ellos sobre el naufragio del “Memphis”. Edward L. Beach Jr. dejó el servicio activo en 1966 y como su padre lo hizo en el empleo de capitán de navío, pero al menos pudo ver reconocida antes de morir hace un par de años su trayectoria y la de su padre en la nueva sede del US Naval Institute en Annápolis, llamada “Beach Hall” en honor a ambos. Volviendo al “Memphis”, casi todos los trabajos consultados hablan de un posible terremoto/erupción/tsunami o una ambigua “tidal wave”, pero reitero que no hemos encontrado nada similar en los registros. En teoría pura y para ajustarse a los hechos, las olas procederían del sector norte (viento este) de un huracán desplazándose con trayectoria oeste entre las Antillas Francesas y el sur de La Española, aunque nadie lo mencionó. El 28 de Agosto de 1916 un huracán mató unas 50 personas en Martinica y, significativamente, otro ya había causado destrozos en Puerto Rico el día 22, lo que daría la razón a Beach en el asunto del diplomático que se quedó a dormir. El causante del “affaire” protocolario pasó al norte de Santo Domingo en la mañana del 23 de agosto ya degradado a simple tormenta tropical, pero el del día 29 lo hizo a unas 160 millas al sur como huracán grado 2 y con vientos de 85 nudos/157 km/h, justamente hacia las 1400 locales. · John Marriott “Disaster at Sea, USS Memphis”, Ian Allan Ltd, Shepperton, Surrey, 1987 · Kit y Caroline Bonner “Great Naval Disasters, USS Memphis”, MBI Publishing, Osceola, WI, 1998 · Edward L.Beach, “The Wreck of the Memphis”, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1966 · “Alvion P. Mossier Saga” The Suburban Press, 14.08.58, Roxborough, Philadelphia y otras fuentes |

| |

The Loss of the USS Memphis on 29 August 1916 - Was a Tsunami Responsible? Analysis of a Naval Disaster(©) Copyright 1963-2007 George Pararas-Carayannis / all rights reserved / Information on this site is for viewing and personal information protected by copyright. Any unauthorized use or reproduction of material from this site without written permission is prohibited.

INTRODUCTION On August 29, 1916, while anchored off Santo Domingo (Ciudad Trujillo) harbor in the Dominican Republic, the armored cruiser U.S.S. Memphis was struck broadside by numerous storm waves and, finally, by an enormous wave which drove the ship into the rocks on the shore. The damage to its hull and engines was irreparable. A subsequent Court of Inquiry and the court-martial of the captain, attributed the loss of the ship to a tsunami. The following analysis documents that the loss of the ship was not due to a tsunami as the official Navy records indicate and that it could have been prevented with proper planning and vigilance. Human errors and lack of knowledge of a passing hurricane were primarily responsible for the loss of the Memphis. The USS Memphis The USS Memphis was a large 14,500-ton displacement armored cruiser that had been launched on 3 December 1904 and originally named "Tennessee". Her armament included four ten-inch guns in twin turrets, sixteen six-inch guns, and twenty-two three-inch guns. The ship had two steam powered engines and was capable of reaching a speed of 23 knots. The USS Memphis' Mission In 1916, an unstable government and political unrest at San Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) required the dispatch of U.S. Marines to protect U.S. interests on this Caribbean nation on the island of Hispaniola. The USS Memphis was ordered to sail to the harbor of Santo Domingo, the capital, to support the U.S. Marines stationed there. Captain Edward J. Beach, was the ship's commander. Also, the Memphis was the flagship of Rear Admiral Charles F. Pond, the ranking U.S. Navy Commander in the region.or peace-keeping patrol off the rebellion-torn Dominican Republic arrived at Santo Domingo harbor in early August 1929.

In July 1916, the Memphis got underway for the West Indies, arriving at San Domingo on 23 July . the ship was anchored at about 55 ft. depth close to the mouth of Ozama river and near the 1177-ton U.S. gunboat "Castine". Anchorage on this southern side of the island was poor, because of its exposure to storms from the south and the southeast. Weather Conditions at Santo Domingo in August 1916 - Ship Preparations This Caribbean island of Hispaniola - shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic - lies in the middle of the hurricane belt and is subject to severe storms and hurricanes from June to October. Concerned that it was hurricane season, Captain Beach proposed to keep four boilers of the Memphis going at all times to enable the ship to get out of the harbor quickly if a hurricane approached. However, because of US. Navy economy measures, Admiral Pond advised Captain Beach to keep only two of the ship's boilers going for auxiliary machinery, but to keep the other four boilers ready in case of emergency. Around August 22, the barometric pressure dropped significantly and the weather begun to deteriorate. Fearing that a storm or a hurricane was approaching, Captain Beach ordered the other four boilers of the ship to be fired and all arrangements to be made to get underway. The feared hurricane did not occur but the preparedness exercise was useful in demonstrating that the required steam pressure to power the ship's engines could be raised in about 40 minutes.

Chronology of Events in the afternoon of 29 August 1916 leading to the Loss of USS Memphis

Satellite photo of the Santo Domingo coast where the USS Memphis perished. 29 August 1916 - The few days after 22 August 1916 were uneventful. Both the Memphis and Castine were riding gently in smooth sea, anchored off Santo Domingo. No storm warnings had been received. However, in the early afternoon of 29 August, even though there was no wind, suddenly the waves became significantly higher. Both the Memphis and Castine begun to roll considerably at their anchorages. Long period waves could be seen coming into the harbor from the east and breaking on the rocks. 15.30 - Concerned about the increasing wave activity, an order was issued to the engine room of the Memphis to raise steam pressure. However, major difficulties were reported from the engine and boiler rooms. Water spray was entering through the ventilators on the ship's deck which had not been properly secured. Some of the ventilators on the deck were subsequently shut off, but a lot of water had already entered the engine rooms, creating problems in raising steam pressure. The engine room reported to the bridge that there would be adequate steam pressure from the four boilers to power the engines by 16.35. 15.35 - 15.40 - In the next few minutes the swells in the harbor increased considerably. The Memphis was rolling very heavily and seas were now covering her decks. Spray continued to come down the ventilator funnels. According to officers on the bridge, the waves were so enormous that the ship's keel bumped the seabed once or twice. Given the fact that the ship was presumably anchored in 55 feet of water, this meant that the waves must have been about 40 feet in height. 16.00 - Huge breakers capsized a motor launch returning to the Memphis. There was nothing that could be done to help the crew and passengers struggling in the water. By that time, the gunboat Castine had managed to increase steam pressure, start its engines and raise her anchor. In an effort to rescue those in the water, the gunboat came into the surf. However, the seas were too rough to lower a boat and the Castine got dangerously close to the rocks. Fearing that Castine may end up on the rocks, the rescue effort was abandoned but life jackets were thrown in the water. Castine's commander ordered to head out. The battered gunboat struggled past the Memphis, but managed to get safely out to deeper water.

With each wave, the ship appeared to be lifting and dragging towards the rocks on the shore. Captain Beach ordered the drop of a second anchor, but the order was canceled when the engine room informed him that steam pressure would be adequate in five minutes to start the engines. With the ship rolling that much and the seas washing over the decks, attempting to drop the second anchor was impossible. 16.35 - An immense wave estimated to be about 70 feet in height was seen approaching the harbor. 16.38 - The engine room could not generate sufficient steam pressure for the engines. The ship's anchor cable was straining and appeared that it would break. With only 90 lb. of steam pressure, Captain Beach had no choice and could not wait for more steam. In an effort to at least turn the ship's bow into the approaching huge wave, he ordered the starboard engine full astern and the port engine full ahead. It was a futile effort. There was simply not sufficient steam pressure to turn the ship ninety degrees and complete the maneuver. 16.40 - The enormous wave was quickly approaching the Memphis. It could be seen churning sediments of sand and mud from the sea bottom. It appeared that it would hit the ship broadside - the most vulnerable position. The shallower water depth had slowed the wave down a bit but its height had increased. In front of it, a 300 ft long trough had formed. As the wave got closer to the Memphis, its peak begun to break. The top of the breaking crest was now about 30-40 feet above on the ship's bridge. The wave form appeared to consist of three distinct steps, each separated by a large plateau. The huge wave broke thunderously upon the Memphis, completely engulfing it. Two seamen trying to release the second anchor were washed overboard. The wave's impact injured members of the crew. Other crew members were injured or killed by steam or by steam inhalation when the ship boilers exploded. The ship did not capsize but recovered to an upright position but hit bottom hard, which normally would be about twenty-five feet below her keel. The battering caused great damage on her hull. 16.45 - Slowly, dragging her anchor, the Memphis struck the first rocks at about 16.45. As each succeeding wave pounded her, she was forced a little further ashore until her port side crushed against the rocks, which pierced this side repeatedly. The Memphis was still rolling from side to side, although now firmly aground. 17.00 - At about 17.00 the battered ship was given one final push by the waves, thus moving her hard aground on Santo Domingo's rocky coast in water depth ranging from 12-19 feet and only 40 feet from the cliffy shoreline. Large holes in the ship's hull could be seen by observers on the shore.

Actions that followed the grounding of the Memphis are not of direct relevance to the evaluation of causes that caused this disaster and details are omitted since they have been adequately documented in U.S. Navy archives and the literature. It will suffice to say only that, as soon as the Memphis had gone firmly aground, Captain Beach ordered the crew to fully secure the ship with ropes to the shore. This was accomplished with the assistance of U.S. Marines and hundreds of Dominicans on the cliffy shore of the harbor. Then the captain ordered the evacuation of the injured, followed by the evacuation of 850 others. This was done in an orderly and safe fashion, using hawsers on land and ropes. Death Toll and Injuries - Damage to the Ship What had started as a normal routine afternoon on board the USS Memphis on 29 August 1916, in a matter of about one hour, turned into a disaster of major proportions. Forty three people lost their lives that fateful afternoon. Twenty five crew members died when the ship's motor launch capsized in huge breakers at about 14.00, as it was attempting to return to the ship. Another eight members of the crew were lost when three boats sent to sea sank or were wrecked attempting to reach shore after dark. Ten more died either by being washed overboard or from burns and steam inhalation when the ship's boilers exploded. The total casualties,numbered 43 dead and 204 injured. The ship itself sustained irreparable damage. Though she appeared to be nearly normal in appearance above the water, the USS Memphis was a total loss. Her bottom was driven in, her hull structure was badly distorted and her boilers had exploded. Her 23,000 horsepower steam power plant had been destroyed. The Memphis, would never sail again. Although her guns and other components were eventually salvaged, her punctured and twisted hull remained an abandoned wreck on the cliffs of Santo Domingo for 21 years - before being dismantled by ship breakers. Conclusions of the Court of Inquiry as to What Caused the Loss of the Memphis The loss of the Memphis was followed by a Court of Inquiry and the court martial of Captain Edward J. Beach, the ship's commander. The court concluded that conditions had deteriorated very rapidly to save the Memphis. Also, that the heavy rolling of the ship and the flooding from the ventilator funnels was the reason that steam pressure could not be raised in time to fire the engines and head out to sea, as the gunboat Castine had barely managed to do. Complications in the engine room were blamed for the failure. The Court found that Captain Beach was guilty of not keeping up sufficient steam to get underway at short notice and of not properly securing the ship for heavy weather. The huge waves that engulfed and wrecked the Memphis and drowned the sailors were attributed to a "tropical disturbance", a "seismic storm", but also to a "tsunami" that originated from a seismic event somewhere in the depths of the Atlantic Ocean or Caribbean Sea.

Photographs of the USS Memphis Wreck taken in 1917 and Later (U.S. Naval Historical Center Photographs)     Analysis of the Naval Disaster

The Navy's conclusion that the loss of the Memphis was due to a 'seismic storm' or a tsunami was erroneous. There is no such thing as a "seismic storm". Furthermore, no tsunami occurred in late August 1916 in the Caribbean Sea or the Atlantic Ocean. The characteristics of the waves observed breaking on the coastline of Santo Domingo in the afternoon of 29 August 1916 were not those of a tsunami. The Hurricanes of 1916 -Tracks of Hurricanes in 1916 in the Caribbean Sea and the Western Atlantic Ocean Tsunami waves were not responsible for the loss of the Memphis. Most of the historical tsunamis in the Caribbean region have been generated by tectonic earthquakes. A review of historical catalogs of tsunamis does not show an event specifically occurring on August 29, 1916. The only earthquake and tsunami in the vicinity which could have affected Santo Domingo occurred on April 24, 1916 north of Puerto Rico, probably in the Mona Passage. Another earthquake/tsunami occurred in the vicinity of Guatemala/Nicaragua on January 31, 1916. This event could not generate a tsunami at Santo Domingo. A tsunami was generated on the Pacific side of Central America. The waves that resulted in the loss of the USS Memphis were not caused by a tsunami. There were no earthquakes of significance in the region during the latter part of August 1916. Similarly , there were no volcanic eruptions or major underwater landslides. The Navy officers who participated in the Court of Inquiry and the court martial of the ship's captain did not appear to have much technical experience or training about storm-generated waves or tsunamis. In 1916, Oceanography and Meteorology had not developed sufficiently as fields of science. Very little was known about tsunamis or the modes of their generation. Also, it appears that very little was known about tropical storms or hurricanes. There was no effective way of tracking hurricanes or reporting vital weather data to the Navy Command. Weather forecasting was at a rudimentary state and there was no effective monitoring system or synoptic observations which could be shared in real time. Finally, communications were not very good in those days. Thus, it appears that the Navy Command did not even have information on the three hurricanes that had passed close to Santo Domingo in the month of August 1916. In fact, on 18 August, one of these hurricanes had made landfall at Corpus Christi, Texas, and had been responsible for widespread destruction. Even if this information was known, it appears that it was not conveyed to the captains of the Memphis or the Castine at Santo Domingo. The USS Memphis was wrecked by storm waves generated by a passing hurricane The location at Santo Domingo where the Memphis and the Castine were anchored was very vulnerable to approaching storm waves from the east and southeast. The water depth of 55 feet where the Memphis had dropped anchor was too shallow and within the breaking depth zone of potential significant waves of longer period and wavelength, generated by hurricanes. As it will be demonstrated, the series of huge breakers and the enormous wave that wrecked the ship on the afternoon of 29 August 1916 were generated by an approaching hurricane. The most significant of the waves that wrecked the Memphis were generated within this hurricane's zone of maximum winds. Once outside the fetch region of generation, these storm waves had outrun the slower moving hurricane system and raced as swells across the Caribbean and towards the harbor of Santo Domingo. The following is an account of the hurricanes that passed near the Dominican Republic in August 1916 and an analysis of the storm waves of the particular hurricane that caused the loss of the ship.

This region of the Caribbean is in the middle of the hurricane belt and is subject to severe tropical storms and hurricanes from June to October. As shown by the hurricane tracking diagram, there were numerous hurricanes that traversed the region in 1916. Most of them developed in the Atlantic Ocean as tropical storms but when they reached winds of more than 75 miles per hour, they were classified as hurricanes. Three of these storm systems became hurricanes in August 1916. Two of them crossed the Central Caribbean Sea, south of Santo Domingo, and one headed north. Track of the unnamed 1916 hurricane that struck Corpus Christi, Texas in 1916 The first of the unnamed hurricanes in August 1916 (8/12 - 8/19) reached Category 3 and made landfall at Corpus Christi, Texas - causing extensive destruction there. The second unnamed hurricane (8/21 - 8/25) reached briefly a Category 2 status as it passed near the island of Hispaniola, but quickly degenerated into a tropical storm. Finally, the third unnamed hurricane in late August (8/27 - 9/2) reached a Category 2 status with sustained winds of over 100 miles per hour. It passed south of Santo Domingo on August 29. It is believed that it was this hurricane that generated the huge waves at Santo Domingo. Because its waves wrecked the USS Memphis, we shall refer to it as "Hurricane Memphis". The unnamed Hurricane of August 12 - August 19, 1916 As the tracking indicates, this hurricane reached Category 3 status passing south of Santo Domingo on 14-15 of August. It continued in a northwest direction, making landfall at Corpus Christi, Texas on August 18.

However, this hurricane was very destructive in the Corpus Christi, Texas region. In fact it was the strongest storm since the Great Galveston storm of 1900 had struck the area south of Corpus Christi Although this hurricane caused some damage, it moved very fast over the Texas coastal area, thus resulting in low loss of life. Only 15 people died. However, property damage was significant and was estimated at $1,600,000 (1916 dollars). Most affected were the cities of Bishop, Kingsville and Corpus Christi. In Corpus Christi, all the wharves and most of the waterfront buildings were destroyed. There was hardly any property that was not damaged. Most of the damage resulted from the hurricane surge flooding and the superimposed storm waves. Evaluation of Hurricane "Memphis" of 8/27 - 9/02, 1916 As the tracking diagram indicates this particular system developed from a tropical storm on 27 August to a Category 2 hurricane on 29 August. It reached sustained winds of over 100 miles an hour and maximum probable wind speeds and gusts of 125 miles per hour. This was a dynamic storm system which advanced into the Caribbean Basin rapidly. The hurricane's speed of translation eastward is estimated at about 15- 20 nautical miles per hour, since it traversed approximately 400 nautical miles on 29 August. At its closest point, the hurricane center was about 250 nautical miles south of Santo Domingo. The following is tracking information for hurricane Memphis, followed by an analysis of the storm waves it generated.

Time Lat Lon Wind(mph) Pressure Storm type Hurricane "Memphis" Wind Field - Directionality of Hurricane Fetches, Duration and Significant Storm Waves and Swells The hurricane's winds blew in a counterclocwise pattern. Soon after the hurricane crossed the Lesser Antilles islands arc, significant storm waves of longer period begun developing within the radius of maximum winds, within fetches of 10 to 20 nautical miles and over a durations of 1 to 2 hours. As the hurricane progressed westward in the Caribbean in the early morning hours of 29 August, the fetches of maximum winds kept on changing direction in the same counterclockwise pattern. Initially the winds generated huge storm waves from an easterly direction. At the time, the wave field in front and on either side of the hurricane center consisted of locally generated seas and traveling swells from other regions of the storm system. However, in the next few hours, as the hurricane was approaching the longitude of Santo Domingo, additional huge storm waves were generated, not only along the east-west fetches of maximum winds, but along fetches with a southeast - northwest orientation. The longer period storm waves begun to outrun the moving storm system and sorted out as distinct wave trains traveling as swells towards the southern coasts of the Dominican Republic. Because of the hurricane's eastward movement and orientation of the fetches of maximum winds, the waves that were generated became very directional towards Santo Domingo. The direction of approach of converging swells was from the east, from the east south-east, and from the south east. Estimate of the Height and Period of the Most Significant Deep Water Storm Wave Generated by Hurricane "Memphis" - The Killer Wave Based on limited data for this historical hurricane but on certain known parameters of other more recent hurricanes, mathematical modeling can be applied to simulate the near sea surface wind field and to estimate the upper limit of the long period waves generated by this storm system. However, such modeling is a very involved process. For the purpose of the present analysis, an empirical approach is sufficient to roughly evaluate the Rayleigh wave distribution function, and the upper limit of storm wave height variability, as well as the maximum period, wavelength, and deep water height of the most significant of the storm waves. Based on this analysis it can be concluded that it was this significan wave or a very similar long period wave, which combined in resonance with other storm waves, and resulted in the huge breaker that engulfed the USS Memphis at 1640 on 29 August 1916 - wrecking it on the rocks of Santo Domingo. The significant height (Ho) and period (To) of the most significant wave generated in deep water at a point on the radius (R) of maximum wind of a hurricane can be calculated mathematically, provided that the hurricane's pressure differential from the normal (Dp) is known, as well as the hurricane's forward speed, its maximum gradient wind speed near the water surface (30 feet above), and the Coriolis parameter (f) at that latitude. The mathematical equations for this calculation are ommitted here but the results are presented. Based on the limited data available for this August 1916 hurricane ("Memphis" - Category 2 hurricane), and assuming that its radius of maximum winds was about 35 nautical miles away from the storm center (a reasonable approximation for a hurricane of this type), the forward speed was 20 knots, and the barometric pressure differential of about 2.3 inches of mercury, the most significant deep water height (Ho) is calculated to be about 58.9 feet. The deep water period of this significant wave is calculated to be about 16.1 seconds - indeed a long period. Once outside the hurricane region this significant wave maintained its wavelength and period, but attenuated somewhat in height during its travel towards Santo Domingo. Wave Transformation in Shallow Water - Effects of Near Shore Refraction and Resonance In the meantime, the first of the longer period storm waves - which outrun the hurricane system's eastward progression - begun arriving as swells at Santo Domingo at about 1500 on August 29. Up to that time the sea had been smooth and there were no reports of winds or a drop in barometric pressure. At that time, the hurricane's center was fairly far away at about 15.6 N and 67.6 W, approximately 300 nautical miles southeast of Santo Domingo. However, these initial waves that begun arriving at 1500 had been generated much earlier, mainly from east-west fetches when the hurricane was as far as 600 nautical miles away. The swells had traveled almost twice as fast as the overall storm. In the next hour, additional storm waves generated closer to Santo Domingo - but coming from a changing east-southeast direction - begun to outrun the moving hurricane and interfere with swells arriving from the east. The direction of the waves approaching Santo Domingo kept on changing, but when the swells reached shallower water, the bottom effects begun to be felt. Near-shore refraction unified the waves' directional approach towards the harbor of Santo Domingo and the location where the Memphis and the Castine were anchored. Some of the waves that had similar periods and wavelengths arrived in resonance, and begun to superimpose on each other - thus augmenting their heights. The longer period waves begun to break in water deeper than the 55 feet where presumably the Memphis was anchored. These breaking waves, some striking broadside, washed over the decks of the Memphis, and thus water went into the ventilator shafts. This in turn caused the problems in raising steam for the engines of the ship. The anchor was still holding, but probably slightly dragging on the sea floor. Apparently not enough scope had been let out on the anchor's chain. Dropping a second anchor would not have helped the Memphis since not enough scope could be released for the anchor to grab and be effective. The Most Significant of the Waves - According to the crew on the Memphis, a huge wave appeared in the horizon and its height was estimated to have been about 70 feet. This must have been the most significant of the waves generated by the hurricane which was estimated earlier to have a maximum deep water height of 58.9 feet and a period of 16.1 seconds when it left the fetch in the hurricane's region of maximum winds (estimated to have been 125 knots/hour). As this huge wave got close to the Memphis, crew members observed that it had three distinct steps and two plateaus on its forward face. Also, they reported that its crest was preceded by a trough which was estimated to be 300 ft. long. These observations suggest that this wave's overall wavelength was about 600 feet and that two other waves had superimposed on it when refraction begun to take place in the shallows off Santo Domingo. Since the period of this extreme wave was calculated to be 16.1 seconds in deep water (unchanged by refraction), the deep water wave celerity (speed) can be estimated - based on Airy and Cnoidal wave theories - to have been: C=L/T =600/16.1= 37.27 ft/sec (independent of depth). However in water shallower than one half the wavelength (in this case less than 300 feet) refraction by bathymetry and effects of resonance begun to take place - thus combining this huge wave with two other significant, long period waves approaching from different sources and directions. This explains the three steps and plateaus that were observed on the face of the huge wave. The transformation of the huge wave had begun about two minutes earlier. When the wave reached water depths ranging much less than 1/2 its wavelength (much less than 300 feet), the refraction effects became more significant. Its speed was reduced considerably. The wave speed was now dependent on the depth of the water and was governed by the shallow water wave equation, which can be simplified as: C = Square Root of gxd - where d=depth of the water, and g= gravitational acceleration for that particular latitude. Based on solitary wave theory, and without knowing the slope profile off Santo Domingo harbor, an estimate of the breaker height can be made based on the relationship between the breaker height (Hb) to the breaking depth (Db). At the breaker depth, all of the wave's potential energy became forward kinetic energy - much to the detriment of Memphis. The relationship from which the depth of the water where the wave will begin to break can be obtained from Hb=Db/1.28. Since the observation was made by members of the crew that the huge wave was about 30 to 40 feet above the bridge of the Memphis - and assuming that the bridge was about 30 feet above sea level, the height of the wave at breaking, Hb, must have been 70 feet. Thus the huge wave must have begun breaking when it reached a depth of 89.6 feet. Had the Memphis been anchored in deeper water, like 120 feet instead of 55 feet, the entire disaster would have been prevented. The ship would not have sustained the earlier flooding of the engine room through the ventilators by the earlier waves and it would have been able to raise steam and sail to deeper water in a timely fashion. Alternatively, if the Memphis had been anchored in 100 or better 120 feet of water - instead of 55 feet - it would have been able to ride all the swells, including the huge 70 foot wave, without a problem. Unfortunately the Memphis was anchored in too shallow and unsafe water depth. When the huge wave had reached a depth of about 90 feet, its crest peaked and the water particle velocity exceeded the wave's forward velocity (celerity). At that breaking depth, all of the wave's energy became kinetic and a huge volume of water begun to move forward at a speed of 25-30 miles per hour. When this huge breaker struck the Memphis broadside, it engulfed its decks and smokestacks and pushed it onshore with tremendous force. At that point in time, the Memphis was forever doomed. The anchor was of no use. The engines, even if they had more than the 90 lbs of steam pressure, would have not saved the ship. Even if the maneuver of turning the ship's bow into the face of the wave had been completed, it would have been futile within the breaking zone of this huge wave. Neither the engine nor the anchor could have opposed the huge wave force. Human Errors Contributed to the Loss of the USS Memphis Human errors were inadequately addressed by the Navy's Court of Inquiry into the disaster and by the court martial of the ship's captain. Complications in the engine room were blamed for the failure. The Court found that the only human errors responsible for the ship's loss was the captain's failure to keep sufficient steam pressure to get underway at short notice and of not properly securing the ship for heavy weather. However, the Navy's economy measures were the main reason that the boilers of the Memphis were not fired at all times to keep steam pressure up for the engines. The huge waves that wrecked the Memphis at the harbor of Santo Domingo in the afternoon of 29 August 1916 were inacurrately attributed by the Court of Inquiry to a "tropical disturbance", a "seismic storm", but also to a "tsunami". The offiicial Navy records still show that the loss of the Memphis was caused by a tsunami or a tropical disturbance - but without further explanation. As explained above, the waves that wrecked the Mempis were not those of a tsunami but were generated by a hurricane that passed south of Santo Domingo. What is perplexing is that no one made a connection between this hurricane and the huge waves it generated. It is apparent that storms were not properly monitored in 1916 and that communications on weather information were poor. The loss of the Memphis was a considerable disaster but, in fact, it was one that could have been prevented with some rudimentary knowledge of storms, storm waves, and with some additional preparation. The most serious of the human errors that resulted in the loss of the ship was the decision to drop anchor in only 55 feet of water. It was an error in judgment, knowing very well that it was hurricqane season. Anchoring in deeper water would have averted the disaster. From the court martial proceedings, it appears that none of the officers in charge had any training or conception of the speed by which a storm would move, or that significant waves of greater heights, wavelengths and periods could be generated by a distant storm, or that the waves could outrun the storm and be immense at distant locations. No one at that time recognized the potential severity of such waves in shallow water, or realized that such waves transform their potential energy into kinetic forward moving energy once a certain depth is reached. Everyone was aware that it was hurricane season, that the barometric pressure had dropped previously and that there was a possibility of an approaching hurricane and possible waves. They made preparations by firing the engines on August 22nd and preparing for such an eventuality. However, none considered the most simple and inexpensive solution to this potential problem by simply anchoring the ship at 100-120 feet depth and out of harm's way. Lack of proper training on weather and wave phenomena was the most important human error in the loss of the USS Memphis. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Hurricanes of 1916

The Hurricanes of 1916

Tracking information for Unnamed Hurricane (Hurricane Memphis) Passing South of Santo Domingo on 29 August 1916

Tracking information for Unnamed Hurricane (Hurricane Memphis) Passing South of Santo Domingo on 29 August 1916

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario